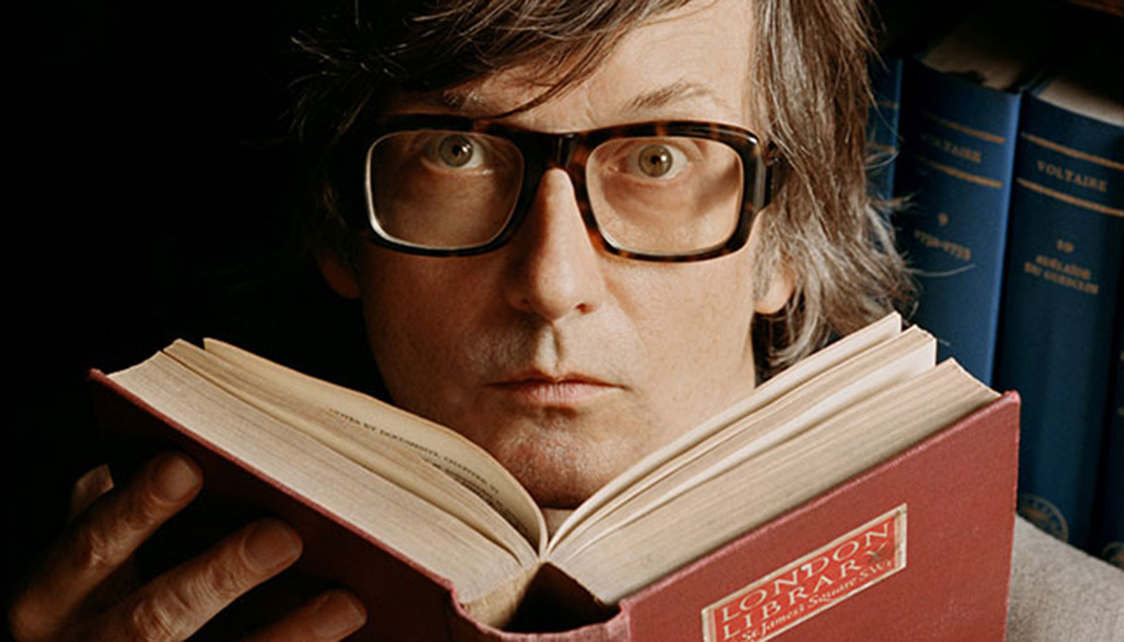

Looking for a creative place to work, study, write or read? The London Library is an independent library with a lending collection of over one million books, 180 desks to work at and creative community of readers and writers.

We offer amazing and quiet spaces to work, think and create in beautiful St. James's Square, for £45 a month, or £22.50 if you're 29 and under.

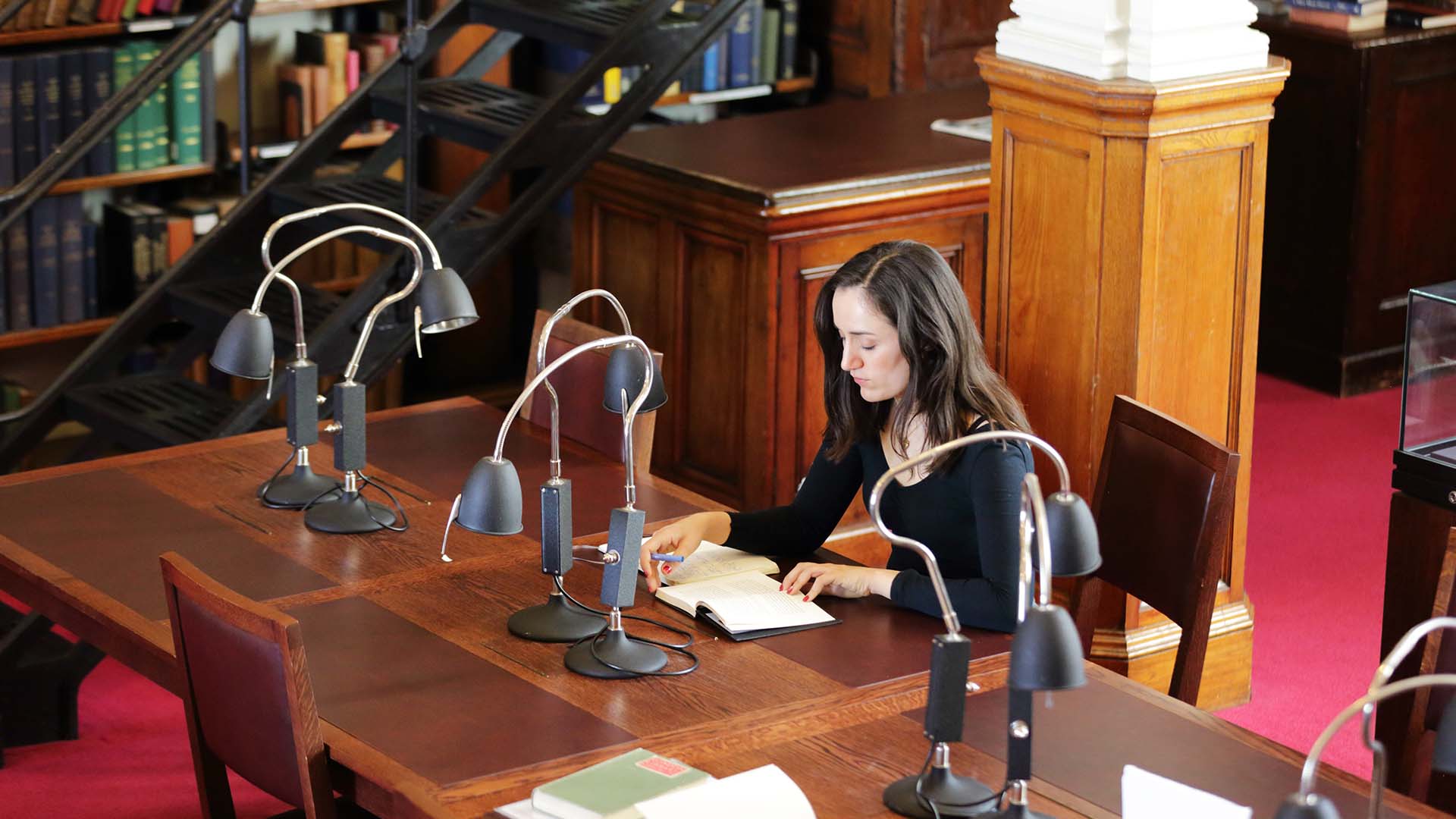

The Library is a magical place with six dedicated reading rooms plus individual desks hidden in the book stacks of our atmospheric building.

By becoming a member of The London Library you will have access to:

- Beautiful and practical spaces in which to read and write, open six days a week with late night openings;

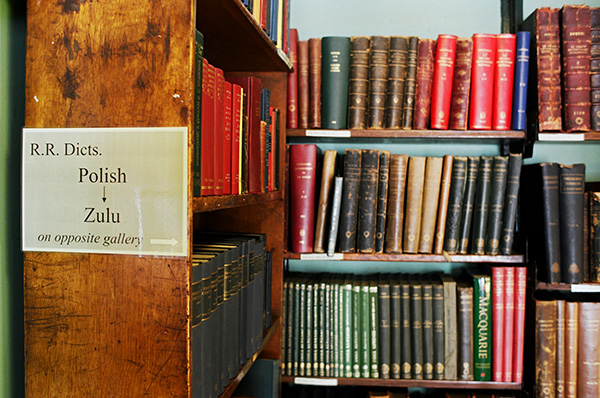

- An incredible collection of 1 million books, with 6,000 more being added every year, almost all of which are available to browse on open shelves and borrow;

- A postal loans service anywhere within Europe, currently with free postage anywhere in the UK;

- Subscriptions to thousands of journals and periodicals and a wide range of digital resources;

- Fiction and non-fiction eBooks;

- Expert staff, always on hand to assist with enquiries;

- Invitations to special events and discounts on our popular public speaker events.

View all of the benefits of membership.

Newsletter

Not quite ready to join? Sign up to our newsletter and receive news, special offers and event updates.

The London Library promises to respect and protect any personal data you share with us. Your information is used to send you the communications you have requested and, personalise your experience of, and communications from, the Library. If you are over 18 we may, in some instances, analyse your data and obtain further publicly available data to help us make our communications more appropriate and relevant to your interests, and anticipate whether you might want to support us in the future.

You can opt-out of most communications or the ways in which we process your data by contacting This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. For full details of how we collect, store, use and protect your data, see our Privacy Policy at www.londonlibrary.co.uk/privacypolicy.

Looking for a creative place to work, study, write or read? The London Library is an independent library with a lending collection of over one million books, 180 desks to work at and creative community of readers and writers.

We offer amazing and quiet spaces to work, think and create in beautiful St. James's Square, for £45 a month, or £22.50 if you're 29 and under.

The Library is a magical place with six dedicated reading rooms plus individual desks hidden in the book stacks of our atmospheric building.

By becoming a member of The London Library you will have access to:

- Beautiful and practical spaces in which to read and write, open six days a week with late night openings;

- An incredible collection of 1 million books, with 6,000 more being added every year, almost all of which are available to browse on open shelves and borrow;

- A postal loans service anywhere within Europe, currently with free postage anywhere in the UK;

- Subscriptions to thousands of journals and periodicals and a wide range of digital resources;

- Fiction and non-fiction eBooks;

- Expert staff, always on hand to assist with enquiries;

- Invitations to special events and discounts on our popular public speaker events.

View all of the benefits of membership.

Newsletter

Not quite ready to join? Sign up to our newsletter and receive news, special offers and event updates.

The London Library promises to respect and protect any personal data you share with us. Your information is used to send you the communications you have requested and, personalise your experience of, and communications from, the Library. If you are over 18 we may, in some instances, analyse your data and obtain further publicly available data to help us make our communications more appropriate and relevant to your interests, and anticipate whether you might want to support us in the future.

You can opt-out of most communications or the ways in which we process your data by contacting This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. For full details of how we collect, store, use and protect your data, see our Privacy Policy at www.londonlibrary.co.uk/privacypolicy.

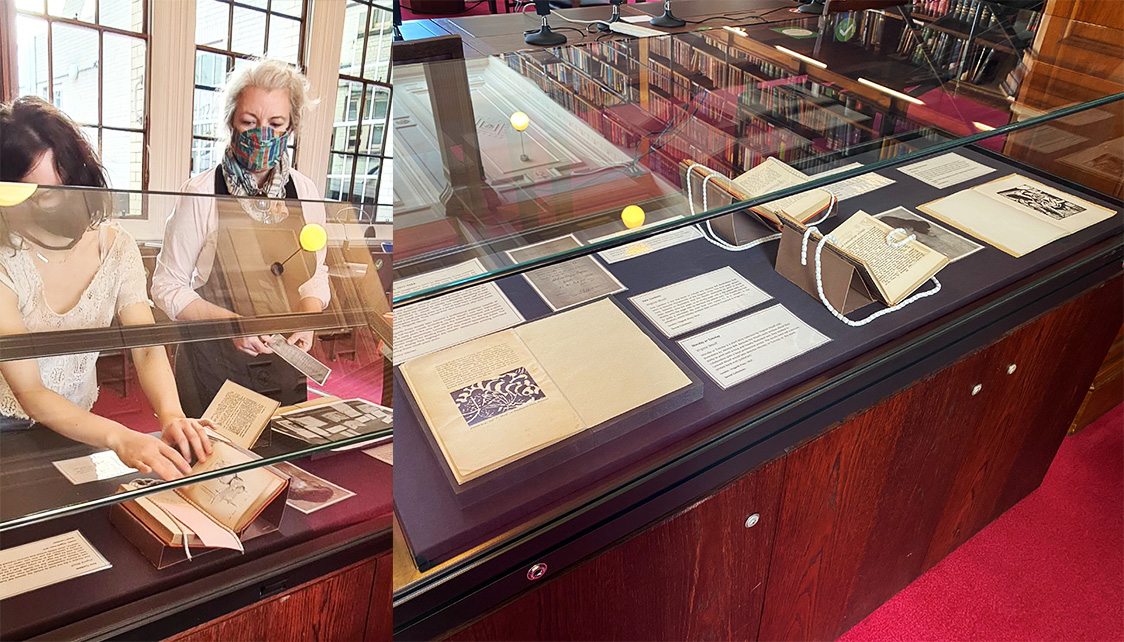

LEFT: Annie Werner (left) arranges a book under the supervision of Conservator Meagen Smith (right). RIGHT: The display in the Reading Room.

The Hogarth Press was a publishing house founded in 1917 by Leonard and Virginia Woolf and was named after their house in Richmond, in which they began hand-printing books. The London Library is fortunate to hold several examples of the Hogarth Press’s rare early work and visitors to The Reading Room will see that a temporary new display has been installed. All of Hogarth items are in our Special Collections and available to view by appointment but we are delighted to be able to share some of our favourites with members that come to work in the Library. Our open stacks also contain extensive holdings of Virginia Woolf’s writing, some of which feature original covers designed by Vanessa Bell, as well as the complete set of Leonard Woolf’s autobiographies as donated by the publisher.

Stack Assistant Annie Werner lays out the display in the London Library’s Conservation Studio.

Virginia Woolf grew up in a London Library household. The novelist was born Adeline Virginia Stephen in 1882 to Julia and Sir Leslie Stephen, both prominent members of the Victorian arts and literary scene. In 1892, Virginia and her elder sister Vanessa (later the artist Vanessa Bell) cheerfully noted the results of a recent election at The London Library in their homemade newsletter:

Mr Leslie Stephen whose immense litterary [sic] powers are well known is now the President of The London Library which as Lord Tennyson was before him and Carlysle [sic] was before Tennyson is justly esteemed a great honour. […] We think that The London Library has made a very good choice.

The Stephen sisters’ newsletter, The Hyde Park Gate News, displays Virginia’s early interest in the materiality of texts. Although The Hyde Park Gate News was handwritten in Vanessa’s cursive, it was styled in columns to resemble a traditional broadsheet and bound in brown cloth. Virginia would later study bookbinding – a popular pastime for Victorian ladies – and spend several months rhapsodising about her new hobby in her diary and letters.

Virginia and Vanessa Stephen joined the Library formally in 1904, shortly after the death of their father. Virginia, then twenty two, listed her occupation as ‘Spinster’ on her joining form. Later that same year she met Leonard Woolf. A fellow London Library member, Leonard Woolf was a former civil servant who had resigned his post in Ceylon in disgust over the brutality of empire. The pair married in 1912.

Virginia Woolf’s first novel, The Voyage Out, was published by Gerald Duckworth and Company in 1915. This contract with Duckworth caused her intense distress. Woolf had always been sensitive to criticism of her work and despised Gerald Duckworth, who was her half-brother on her mother’s side.

Recognising that Virginia was on the verge of a mental health crisis, the Woolfs looked for a constructive outlet for her nervous energy. On her thirty-third birthday, Virginia wrote in her diary that they had decided both ‘to take Hogarth [House], if we can get it’ and to buy a printing press. She continued, ‘I am very much excited at the idea […] — particularly the press.’

The move to Hogarth House was completed in 1915, but Virginia’s fragile mental health prevented them from establishing the Hogarth Press on the site until 1917. The Woolfs purchased a small hand-press from a hobbyist shop in Farringdon and advertised their intent to ‘publish at low prices short works of merit, in prose or poetry, which could not, because of their merits, appeal to a very large public.’ Their first publication was Two Stories, featuring one story by each Woolf.

The Hogarth Press would later become conventional publishing house, but in the hand-press years of 1917-1925 it was decidedly an amateur operation: Leonard handled the printing and administration while Virginia did the typesetting and binding. These hand-press books are all short texts – either short stories or poetry – because setting each page could take upwards of an hour. They are also bound expediently, in stiff paper wrappers rather than board. The early Hogarth Press books are special objects not because they were skilfully or beautifully made, but because of their connection with the hands and mind of one of the twentieth century’s greatest novelists.

We hope many of you will have the opportunity to go and see the items on display in the Reading Room.

© Cultureshock

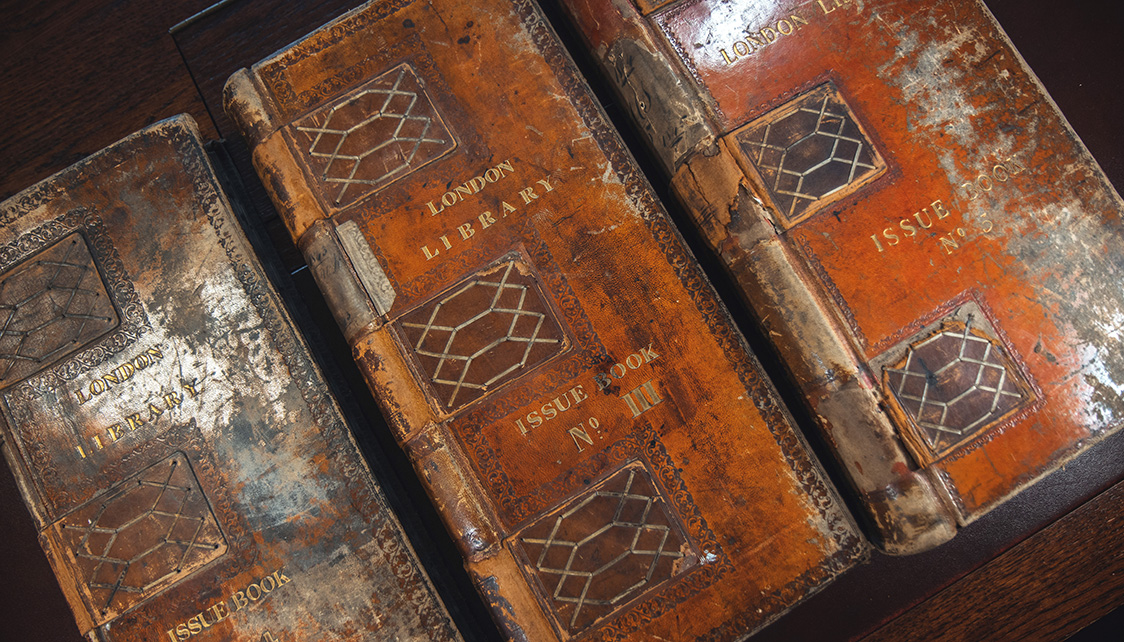

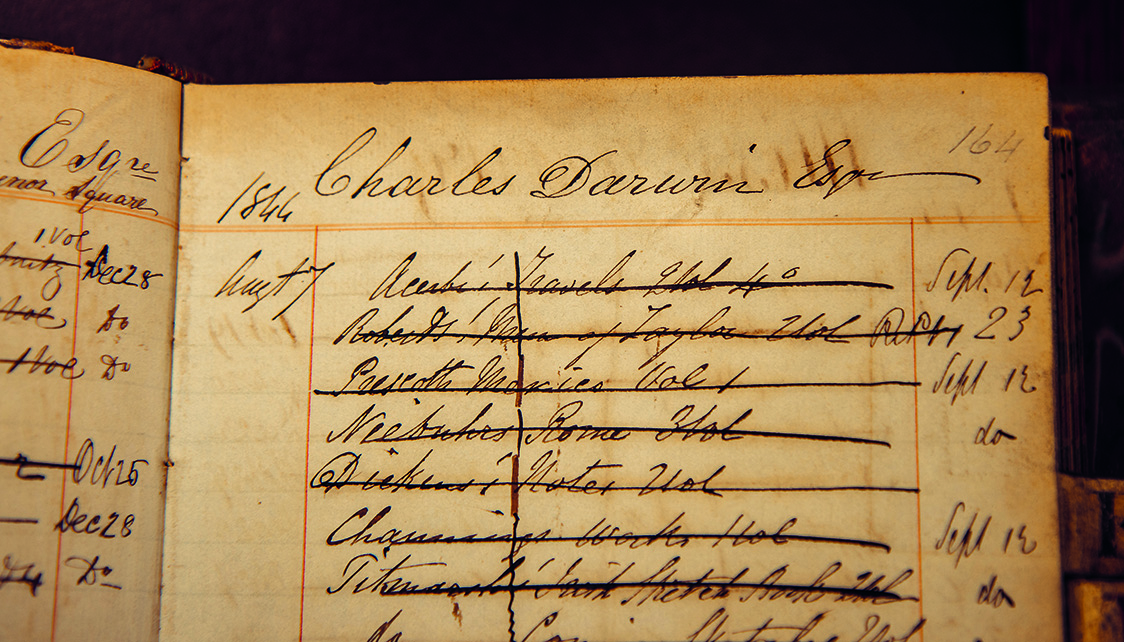

In the Library’s archive are a selection of handwritten Issue Books from the 1840s and 1850s, only a few of which have survived to provide a partial record of early members’ borrowing activities. In amongst them are records for Charles Darwin, listing the books he borrowed during various periods between July 1843 and February 1846 and then during a short, undated period in the early 1850s.

The Library’s recent research into these ledgers – published here for the first time - provides a remarkable insight into Charles Darwin’s reading habits during a busy period in his professional life and reveal him to be a voracious leisure reader.

In the two year period between July 1843 and July 1845, for example, the Issue Books reveal that Charles Darwin borrowed at least 200 books from The London Library, arranging 36 separate visits to collect them. Of the 119 titles mentioned – many of them multi-volume works - the Library has at least 73 of the relevant editions still in its collection today.

© Cultureshock

he London LibraryThe list is remarkable in its range and extent, including diverse titles such as :

- Lives of the Queens of England, by Agnes Strickland

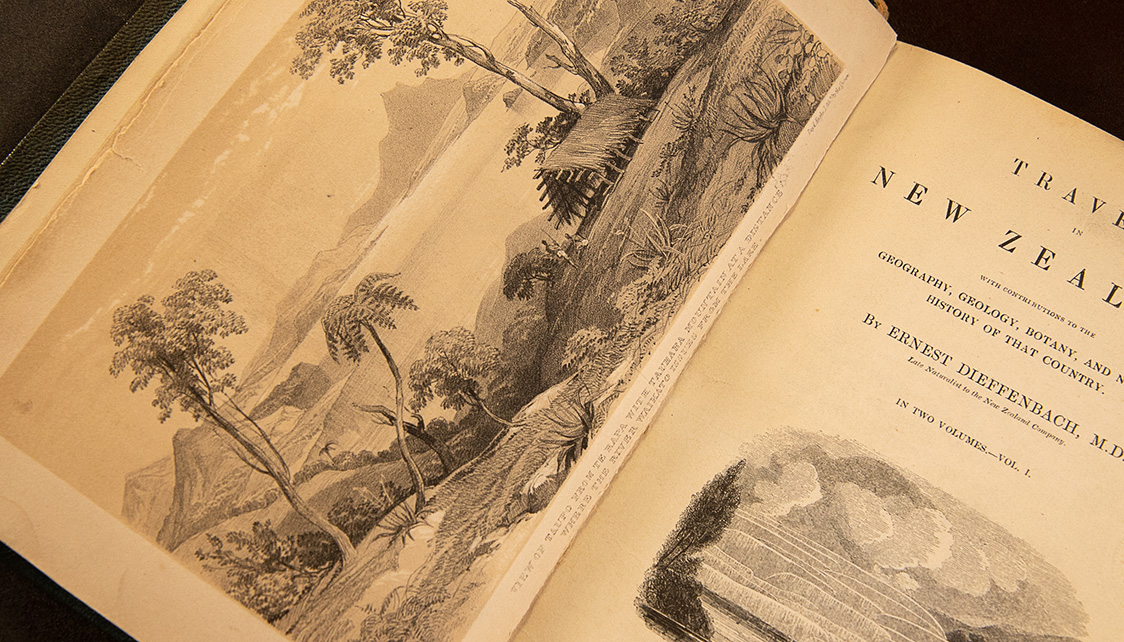

- Travels in New Zealand by Ernst Dieffenbach

- Works and Essays by Montaigne

- Consuelo, Andre and Valentine by George Sand

- Austria by JB Kohl

- The Journal of a Naturalist by John Knapp

- Correspondence of William Pitt

- The History of Greece by William Mitford

- Sermons on Christian Life by Thomas Arnold

- History of the Conquest of Mexico by William Prescott

- Travels through the Alps by James Forbes

- The Bible in Spain by George Henry Borrow

- The Poetical Works of Robert Southey

- The Art of Deer Stalking by William Scrope

The period covered by the Issue Books was a hectic time for the family. Five children were born and during the 1840s Charles Darwin, often ill, produced scientific works on coral reefs and volcanic islands and a revised edition of his bestselling Voyage of the Beagle. Out of the public eye, he was also working on his ‘species theory’, outlining the main ideas in his notebooks by 1842 and writing them up as a fully researched paper which he began sharing with his closest friends in 1844, 15 years before they were eventually published as The Origin of the Species. Exhaustive research into barnacles dominated his time in the late 1840s.

© Cultureshock

In spite of the workload, Charles Darwin and his wife Emma would often spend evenings reading together. It is highly likely that London Library books formed part of this routine, with Charles often borrowing books two or three times a month, taking out several volumes at a time.

The handwritten records in the Issue Books are not always easy to read, especially as entries were ruled through when books were returned. Usually the entries are abbreviated but the book title can be confidently deduced. For example, “Horne Spirit - vol 1” is likely to be A New Sprit of the Age by Richard Horne.

In our lists the information is presented with the handwritten entry shown in inverted commas, followed by what we believe to be the actual book title.