Jane Haslam looks at the story behind one of the most remarkable items in The London Library’s collection – an original, and extremely rare, copy of one of the three editions of Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses known to have been printed in 1517.

Just over five hundred years ago, during Vespers on All Hallows’ Eve in 1517, a notice appeared, nailed to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg (an emerging Saxon town in North-East Germany), inviting discussion over the sale of Papal indulgences in the neighbouring provinces of Brandenburg and Saxony-Anhalt. It was usual practice to advertise topics for academic debate on the church doors of University towns – a notice board for a captive audience. This particular disputation was authored by Fr. Martin Luther, an Augustinian friar, doctor of theology and University lecturer. The text ran to a total of ninety-five items for discussion and, as every school child knows, Luther’s action is considered to pin-point the exact moment when the Reformation began. Within months the German Church was in ferment and Christendom torn asunder. The repercussions have reverberated throughout half a millennium.

The process of affixing notices to church doors was so familiar, so ordinary, that no-one thought to make record of the moment. We are left in the dark as to whether Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses were printed or hand written, whether they were nailed solely to the Castle Church door or onto every other church door in Wittenberg and, most significantly, whether they were nailed or posted anywhere at all. Academics have been, and remain, divided as to the veracity of the story.

The selling of Papal indulgences was an established practice – guilty sinners would part with their money and receive in return letters of safe conduct through Purgatory for themselves and their deceased relatives. The advent of the printing press during the 1440’s had enabled the mass production of indulgences. Producing more meant selling more; boosting the income of the Church. Sales of indulgences had been banned by the Elector Friedrich in Saxony but many Wittenbergers crossed the border into Brandenburg and Saxony-Anhalt attracted by Johannes Tetzel, a well-known indulgence preacher.

The question remains how a pedestrian call for debate became the spark from which the Reformation took light. Luther maintained his innocent intentions, but there can be no doubt that once he realised what was happening, and saw how eagerly and quickly his Theses were shared and re-printed, he undertook to mobilise one of the greatest populist movements in history.

Over the centuries, many words have been written about the Reformation, millions of which have been published over the past year or so alone. A quick scan of the London Library Catalogue turns up dozens of monographs and articles, and in this quincentenary year prominent religious and academic institutions are holding conferences and symposia and mounting real and virtual exhibitions.

The London Library is commemorating too because we hold one of the very few remaining copies of the Ninety-Five Theses that were printed in 1517.

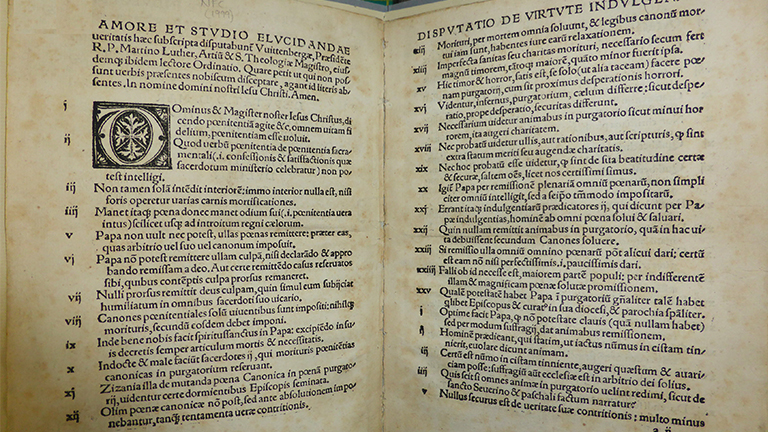

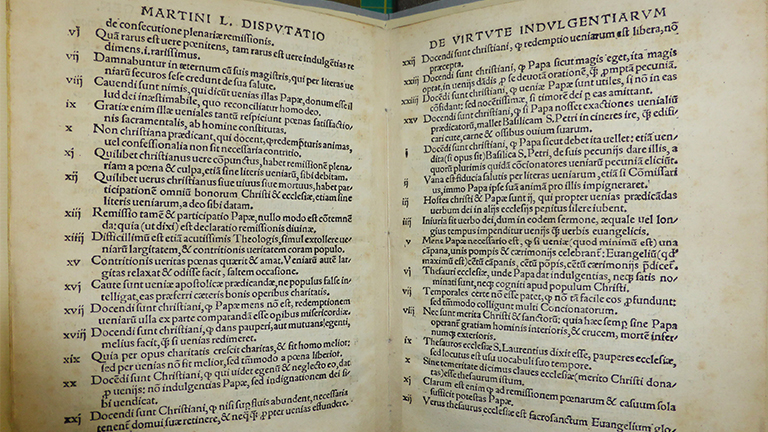

Three editions are known to have been printed at the time and it is thought that each were printed within a fortnight of the nailing of the disputations to the church door. There are two broadsheet or placard editions – attributed to printers Joseph Thanner of Leipzig and Hieronymus Höltzel of Nürnberg – and one quarto or pamphlet edition attributed to Adam Petri of Basel. The Library holds an original from the Petri print run.

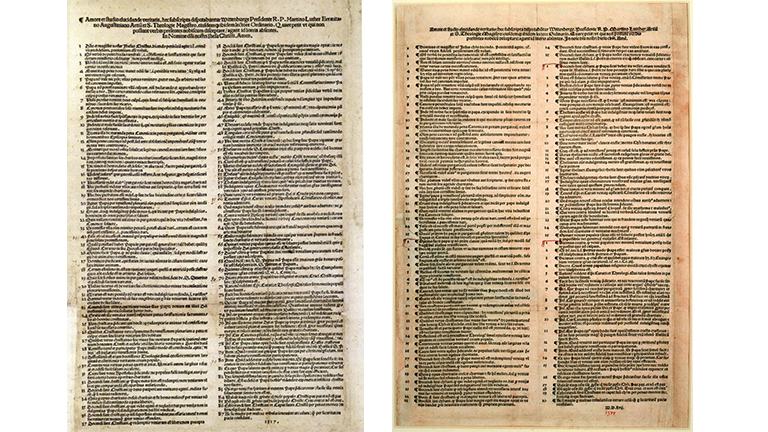

(Left: The Thanner broadsheet – printed by Joseph Thanner of Leipzig – is set with haste and contains numerous setting errors. Right: The Höltzel edition: attributed to printer Hieronymus Höltzel of Nürnberg and the second of the two broadsheet or placard editions)

The three editions show us how swiftly the word was spreading in late 1517. The Thanner broadsheet is set with haste, untidy and full of mistakes. The compositor, clearly under pressure, numbers each thesis in sequence using Arabic numerals but becomes muddled as item 24 becomes 42; 27 becomes 17; and 46 hovers in the middle of item 45, 75 in the middle of 74 leaving a nominal tally of 87. The Höltzel impression is neater and cleaner; an experienced compositor uses Arabic numbers in three sets of twenty-five and one of twenty, a pilcrow marks the beginning of each.The Petri pamphlet uses lower case Roman numerals in sets of twenty-five and twenty, each piece of text is indented. Not as cleanly set as the Höltzel impress, the Petri has a standard print-shop woodcut capital ‘D’ as decoration but the composition is a little loose. During the printing of the Library copy, it appears an enthusiastic or possibly harassed apprentice over inked the type face prior to the paper being laid upon it and the printed sheet was not pulled cleanly from the press. Once the paper had dried our copy was folded twice to make the quarto pamphlet, sent from Petri’s print shop, and distributed from Basel.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to ascertain where our Petri edition went from there: the provenance of the London Library copy is sketchy and open to conjecture. What we know for certain is that The London Library acquired it in 1921. It was delivered to St. James’ Square from the Methodist Central Hall in Westminster which was acting as a temporary repository of The Allan Library. Thomas Allan was a 19th century bibliophile and his passion drove him to scour Northern Europe for any and every book of a religious theme. Charles Theodore Hagberg Wright, Librarian, was eager to acquire this substantial collection in order to supplement The London Library’s German Collections in which he had a specific interest. Thanks to a lack of commitment by the Methodist Conference, and canny manoeuvring by The London Library, a huge resource of 21,500 volumes packed with historically significant gems was had for a song and the Ninety-Five Theses came to The London Library as part of that collection. Today, Allan’s acquisitions not only supplement and enhance the Library’s enviable German Collection but they also form the substantial core of the Library’s Special Collections.

One can only guess where this copy of the Ninety-Five Theses was during the three hundred and fifty years prior to Thomas Allan acquiring it in the early 1860s. Unfortunately, his acquisition records and invoices have not survived, so it is impossible to pin down where any of the collection originated or how much it cost. Thomas Allan stored his collection in packing cases in Baker Street until he gifted it to the Methodist Conference in 1886 where the majority remained packed away, firstly on City Road and then at Methodist Central Hall in Westminster. On transferring to St James’s Square the Ninety-Five Theses was catalogued on 28th October 1921, bound between plain boards and shelved in the recently constructed new glass floored stacks. This seemingly insignificant four-page pamphlet then survived nearly eighty years on the open shelves. When the Anstruther Wing opened in 1999 to house the Special Collections, Allan’s Reformation books were transferred there and it is where our pamphlet now resides in a dust-free, temperature-controlled environment.

It doesn’t matter whether Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the Castle Church door in Wittenberg or not, the story survives, as does one of only a handful of copies of the only contemporary quarto printing. Half a millennium after it was pulled from the press, now newly bound and about to be digitised, the London Library copy of the Petri edition of Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses reaches its quincentenary both treasured and preserved.

The London Library’s copy of the Petri pamphlet edition. The type face was over-inked prior to the paper being laid upon it and the printed sheet was not pulled cleanly from the press.