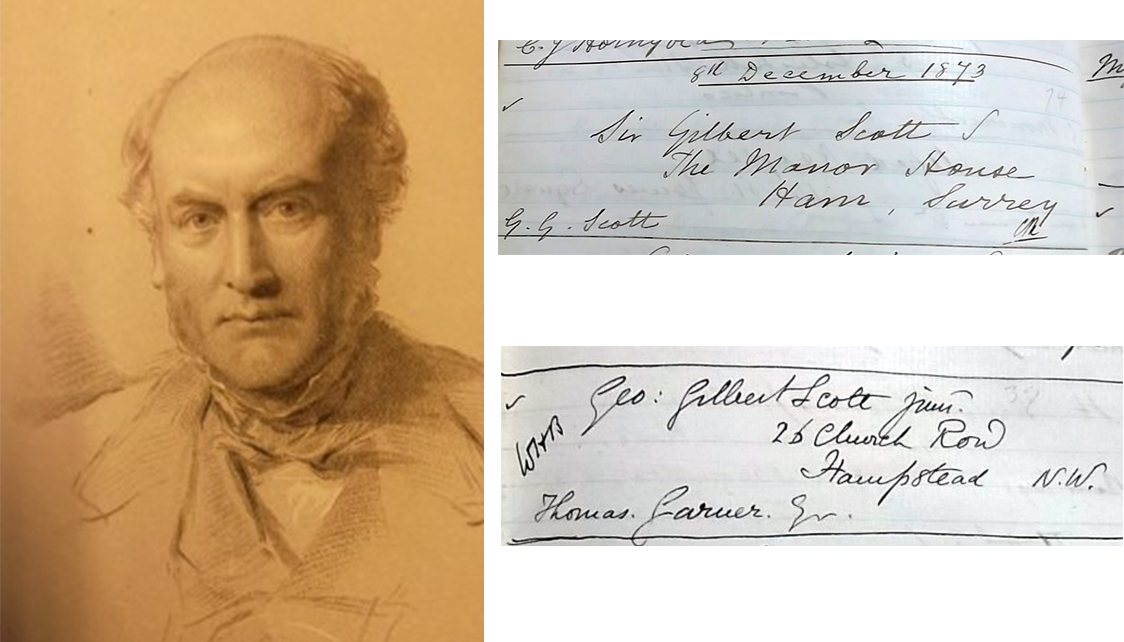

(Left: George Gilbert Scott; Top: Sir Gilbert Scott's membership form from 1873, he was introduced to the Library by his son, George Gilbert Scott Jr; Bottom: George Gilbert Scott Jr an architect and scholar joined the Library in 1872. He was introduced by fellow member, architect Thomas Garner.)

We take a look at the links between The London Library and a distinguished architectural dynasty founded by Sir George Gilbert Scott, the leading proponent of the Gothic Revival.

In London’s swinging sixties, the poet, broadcaster and co-founder of The Victorian Society, John Betjeman, took a stand against the destruction of Britain’s Victorian architectural heritage. After the demolition of Euston Station’s Doric arch, he campaigned to save another iconic Victorian landmark: the Midland Grand Hotel at St Pancras station, as it too tottered on the edge of demolition. It was a building, he said, Londoners enjoyed: a “sudden burst of exuberant Gothic … seen from gloomy Judd Street.”[i]

The hotel was the creation of Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878), the founder of a dynasty of architects which continues today and which stretches from The Midland Hotel “the grandest single monument of the Gothic Revival in Britain”[ii] to the power stations at Battersea “one of the first examples in England of frankly contemporary industrial architecture”[iii] and Bankside (now Tate Modern) taking in the Albert Memorial, Waterloo Bridge, the red telephone box and a staggering number of churches and cathedrals en route.

Sir George Gilbert Scott and his son, George Gilbert Scott Jr (1839-1897) both appear in the Victorian membership records of the Library. George Gilbert Scott Jr joined in 1872 and introduced his father (who was knighted in 1872 and President of RIBA 1873-76) to membership in 1873. Sir George Gilbert Scott’s Personal and Professional Recollections, edited by his son, appeared in 1879: one of the first autobiographies of an architect to be published.

While Sir George Gilbert Scott was an acclaimed Victorian architect, who ran one of the largest architectural practices in Europe, he was not without critics – several of whom are also to be found among the membership records of the Library. The Rev W.J.L. Loftie, the architect J.J. Stevenson and one of the founders of the Arts and Crafts Movement in Britain, William Morris, all articulated a growing unease about architectural restoration, which John Ruskin condemned as a lie declining a RIBA gold medal during Scott’s presidency.

George Gilbert Scott Jr struggled throughout his life with mental health issues and alcoholism. He was confined to Bethlehem Hospital in 1883 and spent several years in and out of hospital. He died of cirrhosis of the liver and heart disease in1897. He was living at the time in his father’s famous secular creation: the Midland Grand Hotel (now renamed the St Pancras Renaissance Hotel). While his professional life was less prolific than his father, his own son, Sir Giles Gilbert Scott (1880-1960) an influential 20th century architect, considered that “Grandfather was the successful practical man, and a phenomenal scholar in Gothic precedent, but Father was the artist”.

Neither Sir George Gilbert Scott nor his son lived long enough to see the unveiling of the London Library’s Victorian steel grilled book stacks, circulating hall or spacious 50 ft long Reading Room in 1898. These Victorian spaces however remain at the heart of the Library’s activities today. Architectural heritage is easy to spot, it connects our physical environment and our daily lives to the past. Betjeman was right about the Midland Grand Hotel which was given Grade 1 listing in 1967. The Victorian Back Stacks of the London Library are also a listed structure, like the Midland Grand Hotel they too exert a powerful burst of Victorian Gothic in the hustle and bustle of 21st century London Library life.