London’s parks, squares and gardens have played an important role over the last few weeks. It seems timely to remember and celebrate Thomas Hill, the Londoner responsible for the first popular gardening books printed in the English language.

Born around 1528, Hill appears to have been more of a literary entrepreneur than a true scholar. He himself confessed to have been ‘rudely taughte’ but he evidently knew enough Italian and Latin to select and translate the works of many classical authors. These translations formed the basis of Hill’s work and while some have accused him of not contributing new knowledge to the subjects he wrote on he did at least have enough of an understanding of these disciplines to choose his sources carefully, the necessary skill to render them into clear English and sufficient honesty to acknowledge in his book those whose works he compiled. He was also shrewd enough to pick popular subjects that would prove commercial successes: physiognomy, astrology, medicine, mathematics, almanacs, conjuring tricks, practical jokes, natural and supernatural phenomena and, of course, gardening.

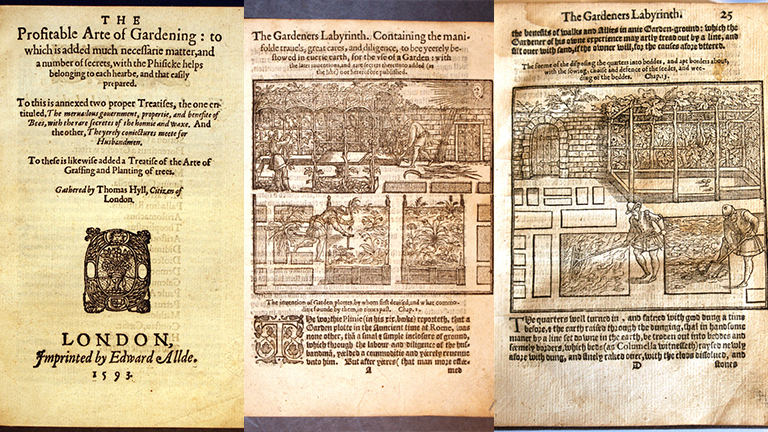

His A Briefe Treatyse of Gardening was first printed without date probably around 1558 and was enormously popular, running to nine editions. Later editions were published under a different title, which spoke of the book’s success, The Profitable Arte of Gardening. It had been augmented by three appendices: The Mervailous Government, Propertie, and Benefite of Bees, With the Rare Secretes of the Honnie and Wax, The Yerely Coniectures Meete for Husbandmen and a Treatise of the Arte of Graffing and Planting of Trees. The London Library edition was printed in the capital in 1593 by Edward Allde, who at the time had his premises ‘in the Fore Street without Cripplegate at the Golden Cup’.

Thomas Hill’s star was rising when his life was cut relatively short in 1574. His second gardening book, The Gardeners Labyrinth: Containing a Discourse of the Gardeners Life, in the Yearly Travels to be Bestowed on his Plot of Earth, for the Use of a Garden … was printed posthumously in 1577.

Hill’s book lists herbs and vegetables giving first the ‘ordering, care and secrets’ and then ‘the physicke helpes’ or medicinal properties of each: ‘… parcely thrown into fish-ponds doth revive and strengthen the sick fish’, melon seeds ‘eaten or drunk doe cause urine, and purge the lungs and kidneis’. He also offers tips for getting rid of pests such as moles, characterised as ‘a disquiet and grief to gardeners’.

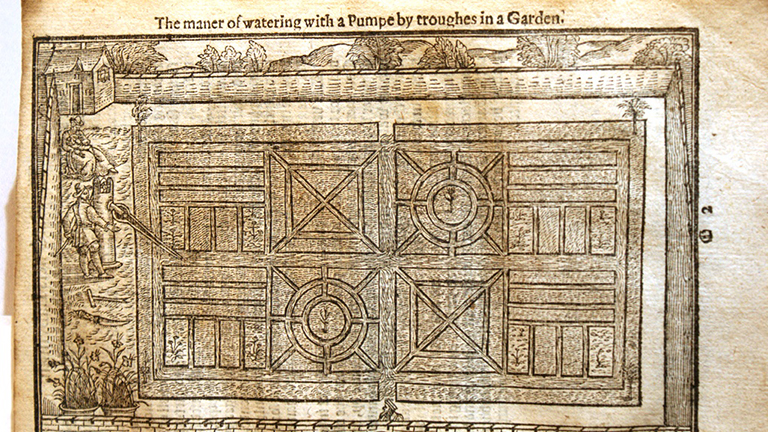

This second work includes many woodcuts, unlike his first book, making it much more expensive to produce and therefore increasing its retail price considerably, which must be a sign of how much Hill’s popularity had grown even after his death. It appears that his status had risen so much that he had even outgrown his name: on the title page Thomas Hill has grown into Dydymus (Greek for Thomas and literally meaning ‘twin’) Mountaine, a rather ridiculous pseudonym that must have nevertheless sounded grand and impressive to a 16th century book buyer. It would be fascinating to know whether this was done in accordance with Hill’s wishes or whether it was the printer’s idea for attracting a wealthier clientele. Either because of or in spite of the ‘mountaine’ effect, or rather because of the quality of the text and charming depictions of Elizabethan gardens, Hill’s second gardening book proved an even greater success than the first one and was reprinted many times. The London Library copy is dated 1586 and is the work of John Wolfe who had his workshop in Distaff Lane, near St. Paul’s.

When Hill died he left many completed manuscripts behind that were never published as well as some unfinished projects. One of the latter was a translation of Swiss naturalist Conrad Gesner’s The Newe Jewell of Health: Wherein is Contayned the Most Excellent Secretes of Phisicke and Philosophie. The translation was completed by his friend, the surgeon George Baker, and The London Library holds a copy of the beautifully illustrated first edition printed by Henrie Denham at the sign of the Star in Paternoster Row in 1576.