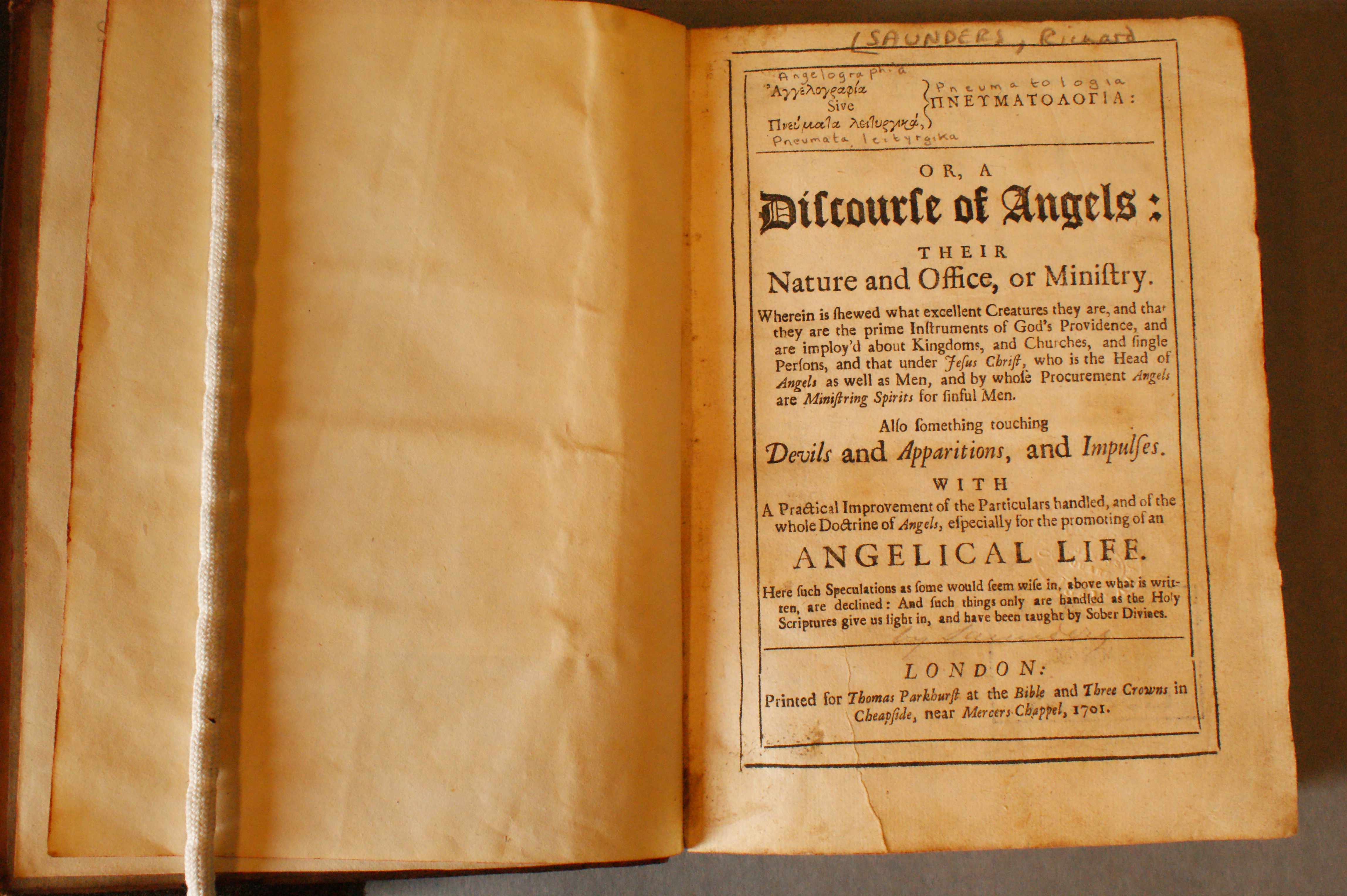

Angelographia sive Pneumata Leityrgika Pneumatologia, or, A Discourse of Angels, their Nature and Office or Ministry, published in London in 1701, was according to Rodney M. Baine “the last thorough treatise [on angels] published in England in the tradition of the previous century”[1]. Baines is referring to the growing scepticism, where angels are concerned, found in 17th and early 18th century England and referred to by the book’s editor, George Hamond, who blames it partly on the ‘irreligiousness of materialists.’

The obscure minister Richard Saunders, author of Angelographia, was apparently the last author willing to proclaim his belief in the existence of angels and show “what excellent Creatures they are …”, albeit anonymously. The book, published nine years after Saunders’ death, appears at first glance to have been written by someone who had intimate, first-hand knowledge of God’s messengers. In fact, Saunders doesn’t claim to have had any personal encounters and cites the Scriptures as his only source. Furthermore, he criticises “the Presumption of the Schoolmen and Papists … who undertake to give the World so particular account of this [the order of angels], as if they had lived among them, and seen their Manners and Government.”

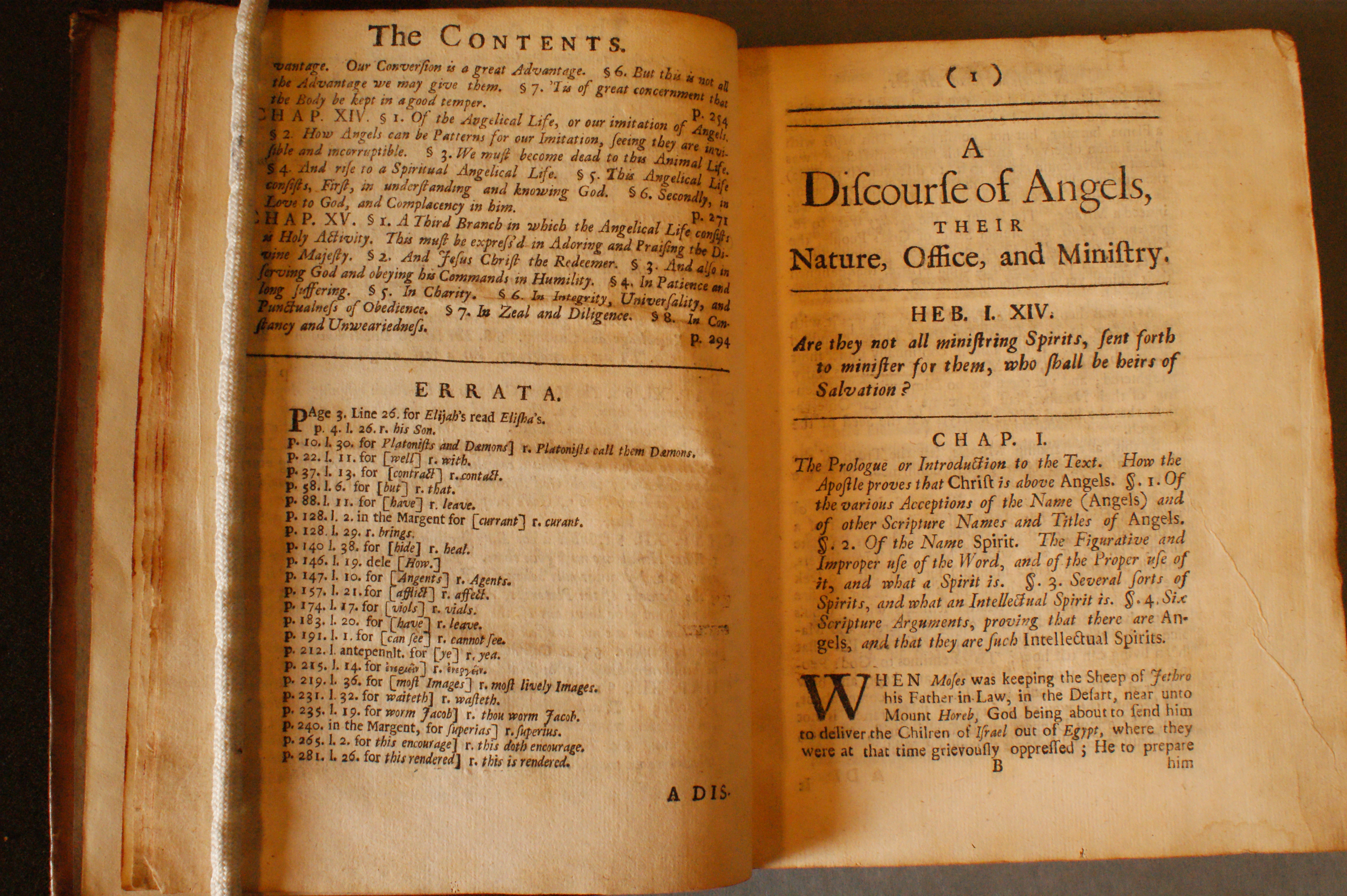

Saunders begins his book by discussing the various appellations given to angels, such as Messengers, Elohim, Morning Stars, Seraphim, Cherubim, Watchers, Thrones, Dominions, Principalities, Powers, Intelligences, Abstract and Separate Forms, Dæmons, and Genii and explains how the names “express somewhat of their nature and properties”. He also writes that there are three kinds of spirit: intellectual, sensitive and vegetative and he states that God and His creations, that is, angels and ‘humane souls’ all belong to the first category. He then goes on to ponder more practical matters, such as whether angels are incorporeal or appear in physical form, the date of their creation, and the extent of their powers.

Saunders claims that they cannot work miracles themselves even though they are enormously agile and as swift as the winds, which is why, the author explains, they are often represented with wings. However, the author does list the sorts of missions angels are sent to perform, from making men prosperous, to warning them of danger and even discovering and restraining enemies, providing comfort and easing the pains of death. Wanting to avoid popish presumption Saunders does not offer any information on angelic hierarchy but when it comes to estimating the number of angels in existence he writes that ‘there are very great Multitudes of them. In all likelihood, as there is a World of Men, so there is a World of Spirits, and they inhabit the Regions above us’. As to the name of their ‘Habitation’, the author tells us that it is the ‘Empereal Heaven or the Heaven of the Blessed’.

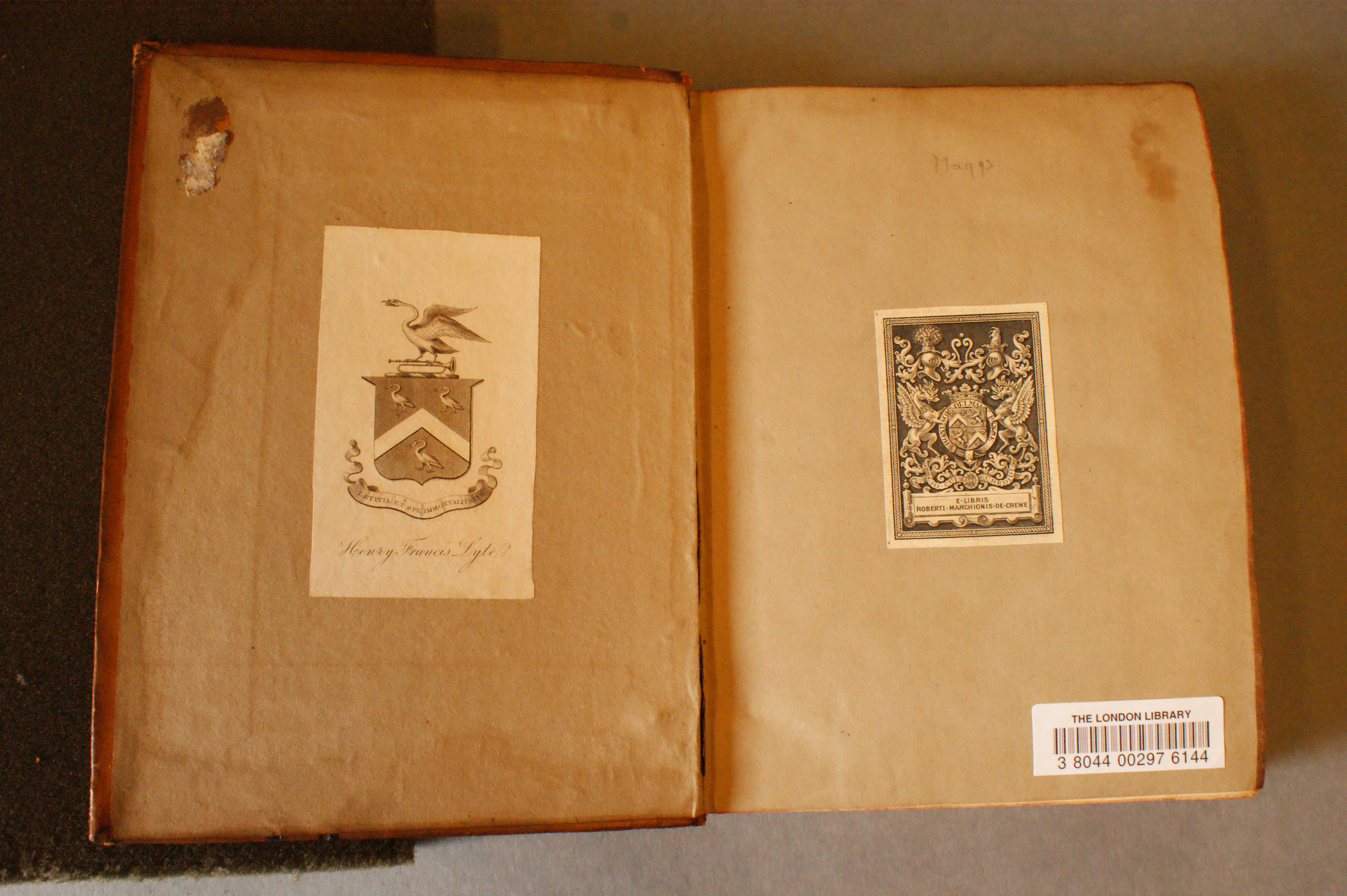

Saunders is in awe of these instruments of God but to him their most important quality is their ‘great love to Mankind’ and he urges men to return that love and not offend these benevolent spirits. His attitude is clearly at odds with that of other Protestant theologians busy attacking the Catholic scholars who wrote on angelology for spending time on ‘nice and idle’ questions. Thomas Aquinas was particularly ridiculed with the question “How many angels can sit on the head of a pin?” after he wondered whether several angels could be in the same place. Surprisingly, given the unpopularity of the subject at the time the book appears to have been something of a success. Quite a few copies have survived and The London Library volume has had at least three famous former owners, two of which who have left their bookplates pasted on the volume’s endpapers.

The first was Henry Francis Lyte (1793-1847), hymn writer and author of ‘Praise, my soul, the king of heaven’ and ‘Abide with me’. Lyte suffered from asthma and his delicate health prevented him from having a stable and profitable career in the Church. He spent much of his life moving from one curacy to another and in his later life he went abroad for long periods of time for the sake of his health. He died at the age of fifty while he was staying in Nice and the following year his extensive library was sold in London.

The man who bought Lyte’s copy of Angelographia was none other than Richard Monckton-Milnes, first Baron Houghton (1809-1885), author and politician and President of the London Library after Thomas Carlyle’s death in 1881. ‘Dickie Milnes’ collected books on many subjects, including theological curiosities and he must have been quite pleased to find Saunders’ treatise on sale among Lyte’s books complete with Lyte’s bookplate depicting a coat of arms with four swans (representing music and poetry).

When Monckton-Milnes died the book passed into the possession of his son, Robert Offley Ashburton Crewe-Milnes, marquess of Crewe (1858-1945). A poor orator, described as being ‘slow of thought and slower of speech’, Crewe allegedly caused one of his listeners to lose her sanity. He preferred reading to public speaking and he certainly had plenty of to choose from among the many books he inherited from his father, even after he disposed of his progenitor’s erotica collection. It is Crewe’s elaborate armorial bookplate that we find on the endpaper facing Lyte’s much plainer ‘ex libris’. Crewe was a reliable public administrator but had an intense dislike of financial matters. This, coupled with extravagant behaviour saw his inherited fortune greatly diminished by the time he died, which may explain why the book did not remain in his family’s possession.

A pencil inscription above Crewe’s bookplate shows us that the book was owned by Maggs at some point and a stamp on the verso of the title page represents the final chapter in the book’s history when it is accessioned by the London Library on 12 March 2002.

To the sceptics who may wonder why apparitions are so rare in modern times Saunders explains that these are no longer as necessary as they once were when the Church was in its infancy and the Scripture was not yet written so that people needed constant ‘sensible entercourse [sic]’ with angels in order to believe in God, whereas now we only need ‘insensible communion’ with them, often in the form of dreams. Saunders finishes his book by exhorting readers to imitate the example given by angels to live a better life ‘in humility, patience and long suffering, in charity, in integrity, universality, punctualness of obedience, in zeal and diligence and in constancy and unwearidness’. This last quality would seem the hardest to attain, particularly for those working long hours and travelling great distances every day to earn a living. Still, as Saunders says: “If we be weary in our bodies, yet we should not in our Spirits. Some services will unavoidably tire the body, but such weariness is none of our Sin, if our Spirits be not tired, but we continue patient in well-doing”

[1] Baine, Rodney M. Defoe and the Angels. Texas Studies in Literature and Language, Vol. 9., No. 3 (Autumn 1967), pp. 345-369